One of the best things about this course and electronic resource management is that no matter what we are studying, we are learning about something that is happening in the library world right this second. I found it really invigorating to feel like what I was learning in class was extra, super relevant to what is happening around us. Etextbooks and ebooks, preservation, "just-in-time" collection development strategies, ereserves and Georgia State...all of these are examples of things that are happening now. I found that no matter where I looked, I was reading something very current and new--in blogs, The Chronicle of Higher Education, or journal articles to support my papers and presentations.

I find that notion really exciting. I am personally very interested in getting people connected to information--that was my inspiration for going to library school in the first place. Eresources are a great way of doing just that--they are convenient and easily accessed from the patron's perspective. But they come with so many thorny issues, like how to keep track of them, how to you get the right licenses, what can you do with them, how do you preserve them, etc. I see it as a really interesting challenge for libraries. How do we make the best of the advantages and limitations of eresources? I think that I am much better prepared to work with eresources in the future after having taken this course, and am not only familiar with what they are but am able to think critically about what they can and can't do for libraries. Who knows...I just might be an eresource librarian in the making!

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Preservation

Our readings for the "Preservation/Perpetual access" week introduced a few key organizations when it comes to preservation, including LOCKSS, CLOCKSS, and Portico. While I think LOCKSS is very useful, and CLOCKSS useful under very specific circumstances, I was really interested in the Portico model because the membership model seems like a good fit for libraries that do not have the resources (in staff, money, or time) to implement a "LOCKSS box." This is obviously a more centralized system than LOCKSS, but it might be the best method for smaller institutions. It will be interesting to see what happens with Portico and if their membership model takes off. It might be difficult for them to raise funding through membership fees, but it does seem like a worthy system.

Our readings for the "Preservation/Perpetual access" week introduced a few key organizations when it comes to preservation, including LOCKSS, CLOCKSS, and Portico. While I think LOCKSS is very useful, and CLOCKSS useful under very specific circumstances, I was really interested in the Portico model because the membership model seems like a good fit for libraries that do not have the resources (in staff, money, or time) to implement a "LOCKSS box." This is obviously a more centralized system than LOCKSS, but it might be the best method for smaller institutions. It will be interesting to see what happens with Portico and if their membership model takes off. It might be difficult for them to raise funding through membership fees, but it does seem like a worthy system.These preservation readings came the same week that I presented on etextbooks. It occurred to me that I was not aware of any model that would preserve ebooks. Our readings discuss these preservation organizations in terms of ejournal content. As it turns out, Portico is introducing new preservation services, including preserving ebooks, starting Jan. 1, 2011. This is great news for libraries that are concerned about their econtent. We are not just working with ejournals--we have these ebooks, etextbooks, datasets, images...the list goes on and on. Each different format could require different preservation strategies, and at the very least, will require working with a larger pool of content suppliers. Librarians had to (and continue to) fight to get perpetual access issues implemented into licenses for full-text databases. They will necessarily have to be ready to negotiate those issues for ebooks, too. Having a centralized system to point to, like Portico, might make publishers more comfortable and make everyone rest a bit more easily.

Playing with my NOOKColor and Overdrive

My fun NOOKcolor is posted to the right. I have been reading Vlad the Impaler: The Man Who Was Dracula with it. I have actually never read a graphic novel before in my life, but I wanted to see what the NOOKcolor could do. It was for the most part, a lot of fun reading the Vlad on the Nook. However, sometimes the text would be so incredibly tiny, and for whatever reason, you can't zoom within this pdf. I am not sure why, since I can zoom within a non-DRM pdf that I uploaded. So that was annoying, but overall, I think the Nook did a nice job of displaying the color images in the novel. No other e-ink readers do this, so I can appreciate it.

My fun NOOKcolor is posted to the right. I have been reading Vlad the Impaler: The Man Who Was Dracula with it. I have actually never read a graphic novel before in my life, but I wanted to see what the NOOKcolor could do. It was for the most part, a lot of fun reading the Vlad on the Nook. However, sometimes the text would be so incredibly tiny, and for whatever reason, you can't zoom within this pdf. I am not sure why, since I can zoom within a non-DRM pdf that I uploaded. So that was annoying, but overall, I think the Nook did a nice job of displaying the color images in the novel. No other e-ink readers do this, so I can appreciate it. I downloaded this ebook from the public library. I also wanted to see how well their system works. I searched around for a graphic novel that looked interesting to me. I thought a history of Vlad the Impaler sounded pretty cool, so I put a hold on it. A few days later, I received an email saying my ebook was ready for download. Downloading the book was really easy--all I needed was the name of my library system and my library card number. (The name of the library system is actually not very obvious--South Central Library System, rather than Madison Public Library, which is how I tend to think of my library. The do offer a link to a map to help you determine which system you are in, but I bet this trips more than a few users up.) The image on the left shows what the Vlad the Impaler page looks like on the WPLC Overdrive site.

I downloaded this ebook from the public library. I also wanted to see how well their system works. I searched around for a graphic novel that looked interesting to me. I thought a history of Vlad the Impaler sounded pretty cool, so I put a hold on it. A few days later, I received an email saying my ebook was ready for download. Downloading the book was really easy--all I needed was the name of my library system and my library card number. (The name of the library system is actually not very obvious--South Central Library System, rather than Madison Public Library, which is how I tend to think of my library. The do offer a link to a map to help you determine which system you are in, but I bet this trips more than a few users up.) The image on the left shows what the Vlad the Impaler page looks like on the WPLC Overdrive site. Y

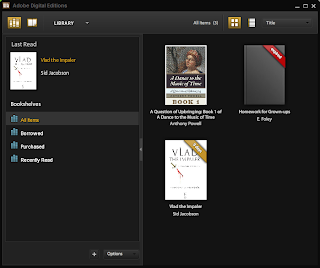

ou also have to download Adobe Digital Editions. I already had this loaded to my computer, so that was not an extra step this time. (And I would say that process is easy, too. You just need your log-in information.) You can see the books that I have downloaded through Adobe Digital Editions--that includes a free ebook from the University of Chicago press, an expired public library ebook, and the still-current public library Vlad the Impaler book. There is a little ribbon across the public library books indicating if they expired or how many days you have left on the book. I have 9 days left on Vlad the Impaler, but I finished last night. If this were a print book, I would just return this to the library so the next person can use it. I know that this book will expire, but sometimes I just like clearing things out and returning them to their "owner." And from a library perspective it would be much better to be able to get the book to the next user. This makes users happy and improves circulation statistics.

ou also have to download Adobe Digital Editions. I already had this loaded to my computer, so that was not an extra step this time. (And I would say that process is easy, too. You just need your log-in information.) You can see the books that I have downloaded through Adobe Digital Editions--that includes a free ebook from the University of Chicago press, an expired public library ebook, and the still-current public library Vlad the Impaler book. There is a little ribbon across the public library books indicating if they expired or how many days you have left on the book. I have 9 days left on Vlad the Impaler, but I finished last night. If this were a print book, I would just return this to the library so the next person can use it. I know that this book will expire, but sometimes I just like clearing things out and returning them to their "owner." And from a library perspective it would be much better to be able to get the book to the next user. This makes users happy and improves circulation statistics. I haven't sat down to read a full-length novel with this little gadget just yet. But I did just download a novel while I am writing this. (Henning Mankell's The Man from Beijing, for the curious.) As with the Vlad book, I had the option of keeping the ebook for 7 or 14 days. I never really know when I will have time for fun reading, so I usually choose 14 days to give me more time. That was too long for the graphic novel, and now I wish I had chosen 7 days so someone else can use it. But 14 days is possibly not long enough for a full-length novel (especially during finals week!). (This book was also one that I had put on hold. I clicked the emailed link to access the book, put it in my cart, changed my mind about downloading it today, exited the system, then I lost my access to the book. I thought the book would continue to be reserved for me for the 3 days mentioned in the "your hold is available" email. I guess if you put the book in your cart, then change your mind, the system does not continue to reserve it for you. I quickly went back to download it once I realized this.)

I would say that, overall, this is a pretty good system for public libraries. I think that Overdrive and Adobe Digital Editions are the key parts in making the system work. I prefer this method of ebook delivery over handing out Kindles to patrons. I totally do not understand why you would want to do that--I prefer this system of downloading the book myself and loading it to my own device. (Spoken like someone who owns one of these newfangled devices.) Now I just wish that my public library offered even more books in ebook format. I chose the NookColor over the Kindle because of its ability to handle epub formats--now I would like even greater selection from my public library, please!

Do you have an ereader that you use to access public library books? How do you like the system? Let me know in the comments below.

Friday, November 26, 2010

Job ads for electronic resource librarians

This week's Albitz and Shelbern (2007) reading pointed out that many electronic resource (ER) librarian positions vary dramatically from library to library. Some jobs focus more on public services while others focus more on technical services. Other jobs throw the "kitchen sink" at their jobs ads and expect the librarian to complete tasks that only a "superhuman" could perform.

I can see how this might happen. It seems like electronic resources management in general is still shaking out...which means that we will probably see lots of differences between jobs ads. As it turns out, I am planning on applying for an "e-resources librarian" at a law school library. (Hopefully I can get that cover letter finished very, very soon...) I thought it would be interesting to take a look at this particular position and relate this week's readings to it.

The main role of the e-resources librarian position at the law school library is to manage the "evaluation, acquisition, licensing, cataloging, maintenance, training, and promotion of electronic and serial resources." The incumbent will also have to collaborate and coordinate with library staff. The next important duty is supporting the research duties of school staff, including faculty, staff, and students conducting statistical research. Much of the emphasis is on helping staff the research community find data sources and to help with statistical analyses. The librarian also provides related instruction, for datasets and statistical software programs (e.g., Stata), but also to advise the research community on acquiring other online resources. The librarian will also have to develop their own web-based projects and will supervise staff. The list of required and preferred characteristics matches to the duties quite reasonably (e.g., MLIS and advanced degree in law or social science required, Drupal and HTML preferred, etc.).

This position seems to fall more strongly in the public services camp than the technical services camp. When I read Albitz and Shelbern's article, I found it surprising that an ER librarian position might fall into public services at all. It seemed to me that managing electronic resources would map pretty well onto more traditional technical service job duties. But this position description helps me to see how it makes sense that an ER librarian might work in a public services capacity. The ER librarian can be the person to both manage the electronic resources, but also promote their use to their community. And who better to instruct users on electronic resources than the ER librarian herself?

The emphasis on statistical support seems to fall somewhere between public services and kitchen sink. It is obviously public services in that you are actively supporting the research community's statistical needs. On the other hand, it feels a bit like a kitchen sink-y in that providing such statistical support is a pretty unique, niche role to fill. It might be hard to find someone who would have experience in both e-resources and statistical support.

On yet the other hand, it seems like there are quite a few jobs ads that require a bit of everything. It seems like this is not at all unusual for librarians. I think that is a pretty interesting and fun part of librarianship--you get to be a jack-of-all-trades that enables access over here, supports scholarship over there, and instructs a bit over here. There is so much change happening in our field that it is necessary to stay flexible and be able to fill multiple roles.

References:

Rebecca S. Albitz, Wendy Allen Shelbern (2007) “Marian Through the Looking Glass: The Unique Evolution of the Electronic Resources (ER) Librarian Position” in Mark Jacobs (Ed) Electronic Resources Librarianship and Management of Digital Information: Emerging and Professional Roles, Binghamton NY: Hayword, pp 15-30.

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

When library stuff follows you around

Yes, it is following me everywhere! I sat down for a nice, quiet lunch in the SLIS commons and as I am wont to do, I opened up The Chronicle of Higher Education, or "People magazine for academics," as one of my friends describes it. Low and behold I came across an article by Jennifer Howard titled, "Publishers Find Ways to Fight 'Link Rot' in Electronic Texts" in the Hot Type column.** The focus was on CrossRef. Lunch was ruined! I kid, I kid.

Howard does a nice job of describing how CrossRef manages citation linking through DOIs. One of the important points that Howard mentions (which I was also mentioned in this week's readings) was the collaborative nature of this whole endeavor. Thousands of publishers need to be on board with CrossRef and the DOI system for it to even work a little bit. The CrossRef association needs to exist to manage all of these DOIs. It is an important point to make. Additionally, much of the initial emphasis was on large publication houses, especially for STEM fields. Now, more and more small publishing ventures are being incorporated (although some find it hard to afford).

Another interesting point mentioned was that DOIs are useful for objects other than scholarly, text-based articles. If you are more interested in linking to data, then DataCite is the DOI consortium for you. It is interesting to see that there are multiple DOI associations. I am curious to know why CrossRef does not handle all DOIs. I imagine that each association has its own strengths that they can apply to different forms of digital objects.

A final interesting point was that the final frontier of DOIs is so-called "gray literature," which are reports not published in a scholarly venue (think government documents and white papers). They are usually housed in a spot on an organization's website and links are probably more prone to breaking than others. Gray literature is still cited, though, and therefor worthy of DOIs.

Howard also mentions Ars Technica's "DOIs and their discontents" blog post. This science-related blog frequently uses DOIs. However, they sometimes fail because the DOIs are sometimes published before the actual article. (Ars gets access to articles and their DOIs before they are published.) So you might try to click on the DOI, but it would just fail since the article hasn't actually been published yet.

I find it fascinating that publishers, organizations, and libraries have come together to create such nifty software that really enables users to find and link to material. DOIs get my stamp of approval!

**I realize that this link will not work. You can try waiting a month for the Chronicle of Higher Ed to plod through its subscription embargo on our licensed database. Or you can try tracking down a print copy for now.

Howard, J. (2010, October 31). Hot Type: Publishers Find Ways to Fight 'Link Rot' in Electronic Texts. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/Publishers-Fight-Link-Rot-in/125189/

Believe me, I find it very ironic that I am trying to discuss the merits of a text that is all about access and connection, and my readers will not even be able to easily click-through to the article.

Howard does a nice job of describing how CrossRef manages citation linking through DOIs. One of the important points that Howard mentions (which I was also mentioned in this week's readings) was the collaborative nature of this whole endeavor. Thousands of publishers need to be on board with CrossRef and the DOI system for it to even work a little bit. The CrossRef association needs to exist to manage all of these DOIs. It is an important point to make. Additionally, much of the initial emphasis was on large publication houses, especially for STEM fields. Now, more and more small publishing ventures are being incorporated (although some find it hard to afford).

Another interesting point mentioned was that DOIs are useful for objects other than scholarly, text-based articles. If you are more interested in linking to data, then DataCite is the DOI consortium for you. It is interesting to see that there are multiple DOI associations. I am curious to know why CrossRef does not handle all DOIs. I imagine that each association has its own strengths that they can apply to different forms of digital objects.

A final interesting point was that the final frontier of DOIs is so-called "gray literature," which are reports not published in a scholarly venue (think government documents and white papers). They are usually housed in a spot on an organization's website and links are probably more prone to breaking than others. Gray literature is still cited, though, and therefor worthy of DOIs.

Howard also mentions Ars Technica's "DOIs and their discontents" blog post. This science-related blog frequently uses DOIs. However, they sometimes fail because the DOIs are sometimes published before the actual article. (Ars gets access to articles and their DOIs before they are published.) So you might try to click on the DOI, but it would just fail since the article hasn't actually been published yet.

I find it fascinating that publishers, organizations, and libraries have come together to create such nifty software that really enables users to find and link to material. DOIs get my stamp of approval!

**I realize that this link will not work. You can try waiting a month for the Chronicle of Higher Ed to plod through its subscription embargo on our licensed database. Or you can try tracking down a print copy for now.

Howard, J. (2010, October 31). Hot Type: Publishers Find Ways to Fight 'Link Rot' in Electronic Texts. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/Publishers-Fight-Link-Rot-in/125189/

Believe me, I find it very ironic that I am trying to discuss the merits of a text that is all about access and connection, and my readers will not even be able to easily click-through to the article.

Thursday, November 4, 2010

ERMes Electronic Resource Management (ERM) Software

Many thanks to Katy K for teaching our class about ERMes Electronic Resource Management (ERM) Software at Murphy Library of the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. The hands-on example really made ERM software much clearer. I have to say, the readings for this week were less than inspired. What a slog. It was really hard to take anything from them. I think you kind of had to know what ERM software looked like already to get much from the readings. But Katy came to the rescue with her demonstration.

I think the demonstration proved that ERMes is simple enough to use. I can't make any claims about other software, but if they are like ERMes, it seems like you could get a handle on the software pretty easily (especially if you are familiar with relational database design). I think the other thing that the demonstration proved is that entering all of your local data into the software could take a really, really long time. Now it does not seem surprising that some libraries might want ERM software, of even to have already bought it, but have no way of implementing it. There could be some real staffing hurdles when it comes to ERM software implementation. It will be interesting to see how licenses get incorporated into ERM software (perhaps via SERU).

I think the demonstration proved that ERMes is simple enough to use. I can't make any claims about other software, but if they are like ERMes, it seems like you could get a handle on the software pretty easily (especially if you are familiar with relational database design). I think the other thing that the demonstration proved is that entering all of your local data into the software could take a really, really long time. Now it does not seem surprising that some libraries might want ERM software, of even to have already bought it, but have no way of implementing it. There could be some real staffing hurdles when it comes to ERM software implementation. It will be interesting to see how licenses get incorporated into ERM software (perhaps via SERU).

Friday, October 22, 2010

Defining authorized users

I'm really interested to see where this ability to tightly define users and who has authorized access to databases goes. There are certainly some pros and cons for such a system.

Tightly defining users: Pros

Tightly defining users: Pros

- It will very likely be cheaper. If libraries work with database vendors to give only pharmacy students access to pharmacy databases, for instance, then the price of the database might go down. This might be of particular importance to an academically diverse research institution, with lots of specific departments and tens of thousands of users.

- Most people will not miss the loss of access to other databases. As a library student, I am mostly interested in the library and information science databases and some social science databases. Pharmacy students are mostly interested in pharmacy databases. I would not lose too much sleep over my loss of access to the pharmacy school databases, and the pharmacy student would probably be okay with losing access to the library science databases.

- This really goes against libraries' commitment to creating access for users. Libraries have been moving to an access rather than ownership model for decades, now. (It is debatable whether or not this is a good idea, but moving to access certainly seems to be the recent and foreseeable trend.) Strictly defining authorized users go against a core mission of the library by limiting access. (Although, see Pros #2.)

- There might be a handful of people who would lose access to databases that are critical to their research, simply because their credentials put them in the "wrong" department. For instance, a history of science student who studies the history of pharmacies in the United States, would be put at a serious disadvantage if he did not receive access to pharmacy materials. Tightly defining users might put some students and researchers at a serious disadvantage.

- Limiting users to certain databases is moving against a very strong trend towards interdisciplinarity in academia. More and more often, university researchers are working across disciplines to advance research on specific problems (e.g., public health, crisis management, global warming, etc.). Limiting access to databases because you are in the "wrong" department could stifle interdisciplinary research. An new example of an institute that would pose a more extreme problem is the Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery, which is both interdisciplinary and a public-private partnership. (Read: some of it could be defined as commercial activity.) How would such a varied institute fit in as an "authorized user"? Sounds problematic to me.

- This one is the kicker: database vendors are not idiots. They have a bottom line to defend. My gut feeling is that the cost of a database would actually not be that much cheaper if you tightly defined authorized users. The databases are the same and the amount of use is still going to be more or less the same for subject-specific databases. Any cost-savings would surely be modest at best, even if a database goes from being accessible to 100% of the university population to being accessible to 1%. Any librarian that thinks that there would somehow be a 99% discount is totally delusional. It seems like libraries could be giving up broad access (again, related to libraries' missions) for what is probably going to be a meager discount. Database vendors will not likely give up nice profits to cut libraries deals based on authorized access.

Something that I just can't stop thinking about: Value and cost

I keep thinking about the value of information. Value is important for information because it often determines cost. And as we all know, costs for licensed databases are extremely high. How did they get to be that way? How does a journal article go from something that someone essentially gives away to being in a database that costs thousands of dollars? Authors of journal articles generally hand over their material and copyrights to the journal publishers. The publishers then repackage the material into journals, both print and online. Those journals are then put into databases. So a question that I have is if this is the general process for scholarly article publication, then why are some databases so much more expensive than others?

For instance, many chemistry and physical science journals are notoriously expensive. What is so special about these journals, and the databases in which they are distributed? Now, I understand that publishers can make some claims that they add value to the journals. Yes, they might lay out the article and perform some copyediting (maybe). But what is so special about chemistry databases, over say nursing or library science databases (which are generally much cheaper)? Could journal publishers/database providers really be adding that much value to chemistry journals but not to nursing journals? It's really hard to believe.

I also keep pondering the notions of excludability and rivalry. Usually information goods often exhibit characteristics of non-excludability (that is, you don't exclude others from using the good) and non-rivalry (that is, you can share the good and it doesn't get used up). Licensed databases really push information goods into the realm of excludability: if you don't pay for this information, you can't have access to it. The information generally will not lose value if more people know it (although, that really depends on the situation, and would not be applicable to trade secrets for instance.) So we can still share this information (i.e., scholarly journals) without all the knowledge being used up, but now we are strictly delimiting who has access to that knowledge. (This is starting to remind me a lot about that Open Access presentation I did last year...)

All in all, these thoughts bring me back to this idea of value and cost. Information can be free and easily shared. So if that is the case, why are these databases so expensive?

For instance, many chemistry and physical science journals are notoriously expensive. What is so special about these journals, and the databases in which they are distributed? Now, I understand that publishers can make some claims that they add value to the journals. Yes, they might lay out the article and perform some copyediting (maybe). But what is so special about chemistry databases, over say nursing or library science databases (which are generally much cheaper)? Could journal publishers/database providers really be adding that much value to chemistry journals but not to nursing journals? It's really hard to believe.

I also keep pondering the notions of excludability and rivalry. Usually information goods often exhibit characteristics of non-excludability (that is, you don't exclude others from using the good) and non-rivalry (that is, you can share the good and it doesn't get used up). Licensed databases really push information goods into the realm of excludability: if you don't pay for this information, you can't have access to it. The information generally will not lose value if more people know it (although, that really depends on the situation, and would not be applicable to trade secrets for instance.) So we can still share this information (i.e., scholarly journals) without all the knowledge being used up, but now we are strictly delimiting who has access to that knowledge. (This is starting to remind me a lot about that Open Access presentation I did last year...)

All in all, these thoughts bring me back to this idea of value and cost. Information can be free and easily shared. So if that is the case, why are these databases so expensive?

Tuesday, October 5, 2010

Georgia State Update

There are some very recent udpates to the Georgia State case. I suggest that you head on over to Scholarly Communications @ Duke's Going forward with Georgia State lawsuit and LibraryLaw Blog's Who infringed at Georgia State? for more information.

There was a recent ruling on summary judgments for the Georgia State case. An important part of the ruling is that the court did not find Georgia State guilty of direct and vicarious copyright infringement, but the case will continue based on concerns of contributory infringement. Discarding the direct and vicarious copyright concerns is good news for Georgia State. Overall, this recent ruling is more favorable to Georgia State than the plaintiffs. The judge presiding over the case has included discussions of the economics that influence providing resources for students. Also, the judge indicated the plaintiffs have a narrow window for proving infringement. Finally, the judge seemed to look favorably on the fact that Georgia State has since changed its copyright policy that brings it more in line with what other universities do. (See the Duke blog for more info on the details.)

LibraryLaw blog makes an interesting point about indirect infringement: if the university (or here, the individual defendants) are not the direct infringers, then who are? Librarians who did the scanning? The faculty that requested the individual scans? Or the many students who would have downloaded the scans? It's an interesting question that has the potential to influence the case. (One of the things that I have learned about the practice of law in the US is that there is often a very pragmatic approach. Judges often seemed concerned about what will actually happen after a court ruling, and they do not just have an ungrounded-from-reality, theoretical approach.) It seems like it would be crazy to go after each individual who had ever been involved in e-reserves, so I suppose the individual plaintiffs had to do.

LibraryLaw blog also points out an interesting tidbit: turns out that the Copyright Clearance Center is paying for 50% of this legal action. Isn't it upsetting that the institutions who pay CCC are now being indirectly sued by them?

There was a recent ruling on summary judgments for the Georgia State case. An important part of the ruling is that the court did not find Georgia State guilty of direct and vicarious copyright infringement, but the case will continue based on concerns of contributory infringement. Discarding the direct and vicarious copyright concerns is good news for Georgia State. Overall, this recent ruling is more favorable to Georgia State than the plaintiffs. The judge presiding over the case has included discussions of the economics that influence providing resources for students. Also, the judge indicated the plaintiffs have a narrow window for proving infringement. Finally, the judge seemed to look favorably on the fact that Georgia State has since changed its copyright policy that brings it more in line with what other universities do. (See the Duke blog for more info on the details.)

LibraryLaw blog makes an interesting point about indirect infringement: if the university (or here, the individual defendants) are not the direct infringers, then who are? Librarians who did the scanning? The faculty that requested the individual scans? Or the many students who would have downloaded the scans? It's an interesting question that has the potential to influence the case. (One of the things that I have learned about the practice of law in the US is that there is often a very pragmatic approach. Judges often seemed concerned about what will actually happen after a court ruling, and they do not just have an ungrounded-from-reality, theoretical approach.) It seems like it would be crazy to go after each individual who had ever been involved in e-reserves, so I suppose the individual plaintiffs had to do.

LibraryLaw blog also points out an interesting tidbit: turns out that the Copyright Clearance Center is paying for 50% of this legal action. Isn't it upsetting that the institutions who pay CCC are now being indirectly sued by them?

Guest lecturers are a fun alternative to regular lecture!

No offense, dear Professor K, but hey, that was really fun! Many thanks to Ms. C, who came to visit our class. I really enjoyed working on those hypothetical scenarios. Even after several weeks of Electronic Resource Management, plus a course in Information Ethics and Policy, a lot of this stuff is still confusing, or at the very least, not obvious.

How do you really apply fair use standards to e-reserve, and other library, situations? Working with the scenarios really made me realize that there isn't an obvious way to answer that question. I think that for 2 out of the 4 scenarios, I thought, "Well, clearly this is what any library would do." And then Ms. C would say, "This is what we did..." and it was the exact opposite of what I though. I tend to think that I am very pro-fair use and have a "use-it-or-lose-it" mentality. But I found that I tended to give a more-risk averse answer.

I learned that there are "riskier" decisions being made out there than I would have thought. This is apparent from our activity, and also from the Georgia State readings. To which I say, Yay! I think that is a good thing. As representatives of institutions with few resources, we need to take advantage of the few benefits that we have coming our way. (Although, you might ignore the low-resources part altogether and just focus on the fact that we should take advantage of a right built into the law.) That's getting back to that use-it-or-lose it idea. So in the future, I can be reassured that there are institutions pushing back on those who would force an overly broad concept of copyright on everyone else.

How do you really apply fair use standards to e-reserve, and other library, situations? Working with the scenarios really made me realize that there isn't an obvious way to answer that question. I think that for 2 out of the 4 scenarios, I thought, "Well, clearly this is what any library would do." And then Ms. C would say, "This is what we did..." and it was the exact opposite of what I though. I tend to think that I am very pro-fair use and have a "use-it-or-lose-it" mentality. But I found that I tended to give a more-risk averse answer.

I learned that there are "riskier" decisions being made out there than I would have thought. This is apparent from our activity, and also from the Georgia State readings. To which I say, Yay! I think that is a good thing. As representatives of institutions with few resources, we need to take advantage of the few benefits that we have coming our way. (Although, you might ignore the low-resources part altogether and just focus on the fact that we should take advantage of a right built into the law.) That's getting back to that use-it-or-lose it idea. So in the future, I can be reassured that there are institutions pushing back on those who would force an overly broad concept of copyright on everyone else.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

UCITA: This is a terrible idea!

The commercial interests of this world do not cease to amaze!

UCITA is a proposed state contract law that would encourage uniform licensing standards for "information in electronic form," which usually means software and anything subject to click-through or web-wrap licensing. The law makes such non-negotiated licenses even more enforceable, to the benefit of licensors/vendors. Major proponents are large technology companies, including Microsoft and AOL. Who is opposed to it? Almost everyone else! Libraries, retail and manufacturing companies, consumer advocates, and financial institutions all have cried out against UCITA.

It only passed in two states (Virginia and Maryland). "Great, I don't live in either of those states!," you say? Wrong! A software license with a choice of law provision can choose either Virginia or Maryland as the governing state. (Thanks for nothing, Virginia and Maryland legislators!) Consequently, a handful of states have enacted "bomb-shelter" legislation to protect their residents from such shenanigans. (You win my heart again, Iowa!)

Once again, I'm annoyed about large commercial interests taking advantage of a widely distributed, less rich, less powerful group of interests. I can understand that software vendors want to protect their product. But click-through licenses already exist. (Although are not always upheld in a court of law, but often are (ProCD v. Z).) But when the American Bar Association's working group on UTICA says that it "is a very complex statute that is daunting for even knowledgeable lawyers to understand" you know something has gone terribly wrong. When even the lawyers cannot figure out the legalese, the rest of use have no hope! This is bad lawmaking.

Once again we are hitting upon this question of putting too much into licenses/contracts/laws/guidelines/whatever. CONFU ran up against this problem as previously noted. Here, UTICA would likely dissolve the careful balance of federal copyright law in favor of the software companies. Contracts, laws, and guidelines (usually, not always) make things easy by stating an explicit set of rules that coordinate people's actions when it comes to content use. It could be a good thing if everyone was on the same page. But it is a bad thing when there are competing interests--you lose any flexibility and balance by writing such rules down. (And when you are up against Microsoft, how well do you think that will end for libraries?)

UCITA is a proposed state contract law that would encourage uniform licensing standards for "information in electronic form," which usually means software and anything subject to click-through or web-wrap licensing. The law makes such non-negotiated licenses even more enforceable, to the benefit of licensors/vendors. Major proponents are large technology companies, including Microsoft and AOL. Who is opposed to it? Almost everyone else! Libraries, retail and manufacturing companies, consumer advocates, and financial institutions all have cried out against UCITA.

It only passed in two states (Virginia and Maryland). "Great, I don't live in either of those states!," you say? Wrong! A software license with a choice of law provision can choose either Virginia or Maryland as the governing state. (Thanks for nothing, Virginia and Maryland legislators!) Consequently, a handful of states have enacted "bomb-shelter" legislation to protect their residents from such shenanigans. (You win my heart again, Iowa!)

Once again, I'm annoyed about large commercial interests taking advantage of a widely distributed, less rich, less powerful group of interests. I can understand that software vendors want to protect their product. But click-through licenses already exist. (Although are not always upheld in a court of law, but often are (ProCD v. Z).) But when the American Bar Association's working group on UTICA says that it "is a very complex statute that is daunting for even knowledgeable lawyers to understand" you know something has gone terribly wrong. When even the lawyers cannot figure out the legalese, the rest of use have no hope! This is bad lawmaking.

Once again we are hitting upon this question of putting too much into licenses/contracts/laws/guidelines/whatever. CONFU ran up against this problem as previously noted. Here, UTICA would likely dissolve the careful balance of federal copyright law in favor of the software companies. Contracts, laws, and guidelines (usually, not always) make things easy by stating an explicit set of rules that coordinate people's actions when it comes to content use. It could be a good thing if everyone was on the same page. But it is a bad thing when there are competing interests--you lose any flexibility and balance by writing such rules down. (And when you are up against Microsoft, how well do you think that will end for libraries?)

Harris's Licensing Digital Content

This week, we finished reading Lesley Ellen Harris's Licensing Digital Content: A Practical Guide for Librarians (2nd ed.). This book is a good introduction to the nitty-gritty details of licensing in a library setting. It has a very practical focus and would make a good reference book if you were ever to find yourself in a situation where you needed to negotiate a license. I am sure any librarian making acquisition decisions, especially those new to doing so, could learn something from this book.

The bulk of the book outlines the need-to-know aspects of licensing. It has a very introductory and sometimes encyclopedic feel. Key digital licensing clauses and boilerplate clauses each get their own chapters. Chapter 1 "When to License" provides a nice introduction to both the book and licensing in general. However, it seems like many librarians will know when to license, as someone or something is pushing for service--some parts feel a little redundant or obvious. Some of the more interesting parts in this chapter are key elements to look for when licensing, including ease of access, "one-stop" transactions, etc. Harris includes nice lists of things to watch out for when acquiring networked content. I find the section on model licenses very helpful because it lists many positive aspects of model licenses (for instance, industry consistency) and negative aspects (lack of flexibility). It would be good to keep these positive and negative characteristics in mind because they might be easy to miss when using a model license.

Other concepts covered that seemed less obvious included interlibrary loan, libraries being responsible for users, and global use of content. Interlibrary loan is often complicated enough without the additional layer of demands placed by varying licensing contracts. It's a good idea to try and keep those demands simple, so as to not make ILL overly complicated. Another important concern is libraries not being responsible for users. Harris makes a good point by saying that libraries should not promise something that they cannot enforce. If a library has no one to monitor patron use (they usually don't), then they should not agree to do so. I imagine that many content providers would prefer, and perhaps pressure, libraries into agreeing to monitor use. It is important to agree to only that which you can accomplish. Another good point made in the book is use on a global scale. This might mean licensing works that are found in other countries, but also allowing your own patrons to use content outside of your own country. I found myself thinking of my many grad student friends who did their dissertation research abroad and how different their experiences might have been if they could not have accessed UW's databases because they were in another country. Researchers travel abroad to do research frequently enough that it would be hard to ignore them as a patron group. Copyright concerns across countries are also important to keep in mind. There seem to be many places where licensing could go wrong if you were not aware of the various limitations that potentially come with licensed content.

I found Chapter 6 "Un-Intimidating Negotiations" to be one of the more interesting chapters in the book. Harris strikes a surprisingly positive note in this chapter. She takes a tone that most things are negotiable, even the presumed "non-negotiable" parts of a contract. (I think that what she means is that it never hurts to ask--you probably will get a no, but you might get a yes.) She does acknowledge that "Librarians often feel powerless entering into, and during the process of, negotiating. Content owners like publishers and aggregators seem to have all the money and plenty of potential customers (and therefore power), while librarians often have only limited resources. However in a negotiation, you are seeking an end result that works for both parties" (94). I completely agree with the first sentence there. I imagine that many librarians must look at negotiations as a lost cause--the Elseviers of the world have so much money and power, why would they negotiate in good faith with any library, large or small? Harris makes it seem that with good negotiation, libraries and content providers can get what they want out of any deal. My response is: Really? Then why are libraries up in arms over the mounting cost of digital content? I am sure that libraries can get what they want in a negotiation--eased ILL restriction, unlimited access for any user that walks into the library, global use, etc. I bet that the vendors would be happy to agree to those terms. But at what cost? You can only negotiate so much without it costing more and more. (Or alternatively, lose rights or access so that databases costs less.) Harris's peppy tone belies that fact that it is still very difficult to negotiate an inflated bottom line.

Or have libraries just not been clever enough to negotiate harder? I don't really think that is the case. Libraries want to provide as much access as they can afford to patrons who are entirely ignorant of cost. It really does seem like libraries are stick in between a rock and a hard place when it comes to balancing the needs of patrons while negotiating price and rights with content owners. Maybe I am just too pessimistic and cynical when it comes to discussions about vendors, rights, and cost.

All in all, though, I found Licensing Digital Content to be quite handy in a practical way. I think that I could make use of it if I were ever to find myself in a situation that required licensing digital content.

The bulk of the book outlines the need-to-know aspects of licensing. It has a very introductory and sometimes encyclopedic feel. Key digital licensing clauses and boilerplate clauses each get their own chapters. Chapter 1 "When to License" provides a nice introduction to both the book and licensing in general. However, it seems like many librarians will know when to license, as someone or something is pushing for service--some parts feel a little redundant or obvious. Some of the more interesting parts in this chapter are key elements to look for when licensing, including ease of access, "one-stop" transactions, etc. Harris includes nice lists of things to watch out for when acquiring networked content. I find the section on model licenses very helpful because it lists many positive aspects of model licenses (for instance, industry consistency) and negative aspects (lack of flexibility). It would be good to keep these positive and negative characteristics in mind because they might be easy to miss when using a model license.

Other concepts covered that seemed less obvious included interlibrary loan, libraries being responsible for users, and global use of content. Interlibrary loan is often complicated enough without the additional layer of demands placed by varying licensing contracts. It's a good idea to try and keep those demands simple, so as to not make ILL overly complicated. Another important concern is libraries not being responsible for users. Harris makes a good point by saying that libraries should not promise something that they cannot enforce. If a library has no one to monitor patron use (they usually don't), then they should not agree to do so. I imagine that many content providers would prefer, and perhaps pressure, libraries into agreeing to monitor use. It is important to agree to only that which you can accomplish. Another good point made in the book is use on a global scale. This might mean licensing works that are found in other countries, but also allowing your own patrons to use content outside of your own country. I found myself thinking of my many grad student friends who did their dissertation research abroad and how different their experiences might have been if they could not have accessed UW's databases because they were in another country. Researchers travel abroad to do research frequently enough that it would be hard to ignore them as a patron group. Copyright concerns across countries are also important to keep in mind. There seem to be many places where licensing could go wrong if you were not aware of the various limitations that potentially come with licensed content.

I found Chapter 6 "Un-Intimidating Negotiations" to be one of the more interesting chapters in the book. Harris strikes a surprisingly positive note in this chapter. She takes a tone that most things are negotiable, even the presumed "non-negotiable" parts of a contract. (I think that what she means is that it never hurts to ask--you probably will get a no, but you might get a yes.) She does acknowledge that "Librarians often feel powerless entering into, and during the process of, negotiating. Content owners like publishers and aggregators seem to have all the money and plenty of potential customers (and therefore power), while librarians often have only limited resources. However in a negotiation, you are seeking an end result that works for both parties" (94). I completely agree with the first sentence there. I imagine that many librarians must look at negotiations as a lost cause--the Elseviers of the world have so much money and power, why would they negotiate in good faith with any library, large or small? Harris makes it seem that with good negotiation, libraries and content providers can get what they want out of any deal. My response is: Really? Then why are libraries up in arms over the mounting cost of digital content? I am sure that libraries can get what they want in a negotiation--eased ILL restriction, unlimited access for any user that walks into the library, global use, etc. I bet that the vendors would be happy to agree to those terms. But at what cost? You can only negotiate so much without it costing more and more. (Or alternatively, lose rights or access so that databases costs less.) Harris's peppy tone belies that fact that it is still very difficult to negotiate an inflated bottom line.

Or have libraries just not been clever enough to negotiate harder? I don't really think that is the case. Libraries want to provide as much access as they can afford to patrons who are entirely ignorant of cost. It really does seem like libraries are stick in between a rock and a hard place when it comes to balancing the needs of patrons while negotiating price and rights with content owners. Maybe I am just too pessimistic and cynical when it comes to discussions about vendors, rights, and cost.

All in all, though, I found Licensing Digital Content to be quite handy in a practical way. I think that I could make use of it if I were ever to find myself in a situation that required licensing digital content.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

CONFU: No surprise there

So you say that a conference intended to create guidelines for fair use was not successful? That the proposed guidelines did not pass the comment and endorsement process? Get out of town!

I kid, I kid. Kudos to the folks who put this conference together in the first place. Having guidelines for fair use of content is a great idea. I am sure that many people--librarians, educators, artists, content providers of all stripes--would appreciate clearer guidelines. Unfortunately for the CONFU folks, there were several issues already at play. Importantly, the copyright owners and content providers felt like the CONFU guidelines gave away too much, while users felt like the guidelines were too restrictive and that they got too little out of the deal. It seems as though it would be extraordinarily difficult to get people to agree on any terms related to fair use. (I find it hard to imagine almost any negotiations, but I'll get to that more when I discuss Harris's LicensingDigital Content.) Users and content owners are just on such different sides of the spectrum when it comes to using and protecting content. Users, even if they are trying to do right by the content owner by following fair use, are still using (i.e., copying for educational purposes, satirizing, etc.) the content in a way that content owners might not necessarily want. If it were up to the content owners, there might not be fair use at all. If it were up to the users, fair use rights might be greatly expanded.

Those two positions are hard to negotiate (again, which is why it is no surprise that this meeting of the fair use minds ended in failure). But that is why we have government and laws, no? That is why fair use is encoded in statutes, court cases, etc., am I right? Ideally, courts and lawmakers will try to find a reasonable balance between the needs of users and content owners (although this seems hopelessly naïve). Fair use has no "bright line rules."* It is up to the content users and owners to do what they will and duke it out in court if there is a disagreement. This means that no one side will have their needs enshrined in fair use law. The gigantic downside is that you need to go to court to have someone tell you who is right...and now we are back to where the idea for CONFU started, I'm sure. This begs the question of should there be "bright lines" for fair use? I think the answer is no. I think one side would inevitably lose something automatically. CONFU guidelines skirted too close to this notion of laws set in stone, and I think that is why the meeting disintegrated.

CONFU points out there there is a world of disagreement when it comes to fair use standards. For now, users are relegated to using their own (hopefully) good judgment when re-using materials.

*Incidentally, that is one of my favorite phrases learned in library school.

I kid, I kid. Kudos to the folks who put this conference together in the first place. Having guidelines for fair use of content is a great idea. I am sure that many people--librarians, educators, artists, content providers of all stripes--would appreciate clearer guidelines. Unfortunately for the CONFU folks, there were several issues already at play. Importantly, the copyright owners and content providers felt like the CONFU guidelines gave away too much, while users felt like the guidelines were too restrictive and that they got too little out of the deal. It seems as though it would be extraordinarily difficult to get people to agree on any terms related to fair use. (I find it hard to imagine almost any negotiations, but I'll get to that more when I discuss Harris's LicensingDigital Content.) Users and content owners are just on such different sides of the spectrum when it comes to using and protecting content. Users, even if they are trying to do right by the content owner by following fair use, are still using (i.e., copying for educational purposes, satirizing, etc.) the content in a way that content owners might not necessarily want. If it were up to the content owners, there might not be fair use at all. If it were up to the users, fair use rights might be greatly expanded.

Those two positions are hard to negotiate (again, which is why it is no surprise that this meeting of the fair use minds ended in failure). But that is why we have government and laws, no? That is why fair use is encoded in statutes, court cases, etc., am I right? Ideally, courts and lawmakers will try to find a reasonable balance between the needs of users and content owners (although this seems hopelessly naïve). Fair use has no "bright line rules."* It is up to the content users and owners to do what they will and duke it out in court if there is a disagreement. This means that no one side will have their needs enshrined in fair use law. The gigantic downside is that you need to go to court to have someone tell you who is right...and now we are back to where the idea for CONFU started, I'm sure. This begs the question of should there be "bright lines" for fair use? I think the answer is no. I think one side would inevitably lose something automatically. CONFU guidelines skirted too close to this notion of laws set in stone, and I think that is why the meeting disintegrated.

CONFU points out there there is a world of disagreement when it comes to fair use standards. For now, users are relegated to using their own (hopefully) good judgment when re-using materials.

*Incidentally, that is one of my favorite phrases learned in library school.

Electronnic Resource Management and Licensing

Hi there! Welcome to my re-purposed blog, Nerdy/Cool Scale. This blog will collect my thoughts on the readings for LIS 855 Electronic Resource Management and Licensing, held at the School of Library and Information Studies (SLIS) at UW-Madison. We will be covering exciting topics, such as:

- copyright

- licensing (as it pertains to electronic resources)

- e-reserves

- pricing models and consortial arrangements

- distance education

- technological protection measures (digital rights management)

- data standards

- e-books

- perpetual access

- many other nerdy AND cool topics!

Tuesday, June 1, 2010

Nerdy/Cool Scale

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)